CCPA will hit your dev team harder than GDPR. Here’s why.

While GDPR gets the lion’s share of the coverage, California recently passed an extremely powerful, far-reaching law, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), that will likely drive even more change than the GDPR. Technically, it’s only a California law, but it’s expected to have a much broader impact because it’s one of the first such laws in the US, and it has a very broad definition of sensitive data.

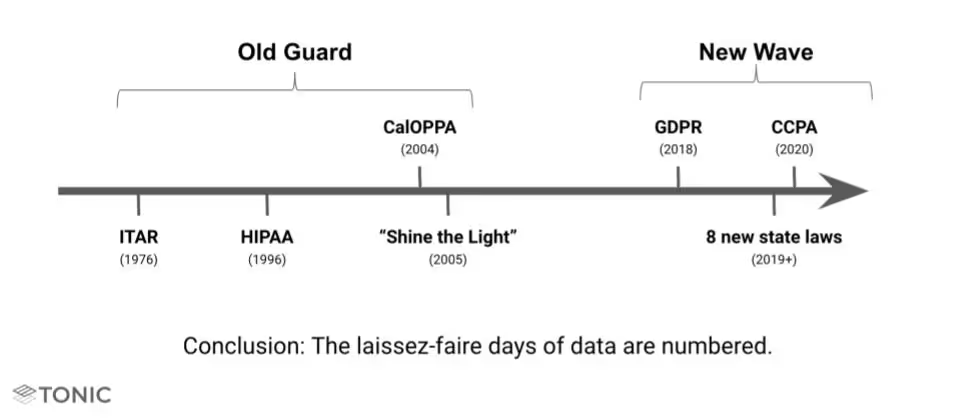

Regulations around how companies can use data have existed for decades and typically fall into one of two categories:

- Strict and Narrow (e.g. HIPAA and ITAR)

- Weak and Broad (e.g. CalOPPA and “Shine the Light”)

Unlike the older laws, however, the new wave of regulations (GDPR, CCPA, SHIELD, etc.) are both strict and broad. In other words, these new regulations apply to most companies, cover most common business data, and outline strict penalties for enforcement. As we’ve seen with GDPR, companies cannot afford to sit around and ignore these new laws.

How the CCPA came into being

It’s easy to assume that the accelerating rise in data breaches and recent revelations of how large companies are using data (e.g. Facebook & Cambridge Analytica) were the primary drivers behind this law. While those had an influence, the genesis of the law has a much more interesting story. CCPA started as a ballot initiative funded by a wealthy CA voter named Alastair Mactaggart. He started worrying about data privacy after talking with a Google engineer and spent nearly $3.5 million in 2017 and 2018 to place an initiative on California’s November ballot.

What Mactaggart and his team initially drafted diverged dramatically from conventional approaches to privacy protection, with very draconian penalties. Fearful of this initiative being passed by voters in Nov 2018, state lawmakers and big California-based tech companies negotiated a deal with Mactaggart that they would pass what would become the CCPA if he removed the ballot initiative. The legislation passed in June 2018, just one week after its first drafting (and hours before the deadline to remove Mactaggart’s ballot initiative). In contrast, the GDPR took almost 4 years to pass into law from its initial proposal.

Since CCPA was rushed out the door, there were a number of inconsistencies and drafting errors in the original law. The expectation was that it would get cleaned up, and that’s already happening. A small amendment was passed in September, though it mostly served to correct grammatical errors. We expect there will be several more amendments and clarifications.

Who must comply with CCPA?

For-profit companies that do business in the state of CA and meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Have annual gross revenue >$25M

- Process personal information of >50k consumers, households or devices

- Derive >50% of revenue from selling PII

Some interpret the above to mean that basically anyone who does business in California will have to comply with CCPA. This is because it defines the “consumer” to be anyone in CA, not just people in a commercial relationship, and CCPA’s definition of PII is equally broad, as you’ll see below. So if 50k California residents visit your website and you log their IP addresses, or almost anything about them, CCPA will apply to your business (or at least to how you handle data for those CA residents).

If your company qualifies, which it most likely does, you will need to inform consumers about the type of personal data you collect and its business purpose.

CCPA has a very broad definition of sensitive data

One of the ways in which CCPA differs vastly from almost all other privacy laws is in the incredibly broad range of data that it covers. Specifically, the law covers “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.” Keep in mind that these consumers and households are anyone in CA, not just people in a commercial relationship with your business.

This definition of data includes:

- Identifiers

- Geolocation data

- Browsing history, search history, interactions with ads and apps

- Biometric data

- Purchase history or tendencies

- Education information

- Employment-related information

- Inferences drawn from such information (consumer preferences, characteristics, etc.)

- Demographics

What’s interesting is that the law specifically states that CCPA does not restrict a business’s ability to collect, use, retain, sell or disclose consumer information that is de-identified or aggregated. It defines de-identified as “information that cannot reasonably identify, relate to, describe, be capable of being associated with, or be linked, directly or indirectly, to a particular consumer.”

Enforcement and provisions

While the law goes into effect on January 1, 2020, it has a year-long lag, so it’s possible that data generated in 2019 could be covered.

In addition to regulations on data handling for companies, the law grants a number of rights to the consumer:

- Right to information

- Right to be forgotten

- Right to opt out of sharing with third parties

- Right to equal service

- Right to data portability

- Ability to sue if data isn’t properly protected

These are largely similar to GDPR, with the notable exception of the requirement of a large “Opt Out Button” to prevent a company from selling your personal information. Companies aren’t allowed to discriminate in price or services if a customer opts out. The only exception is if the service directly requires the data that the consumer barred from sharing. In that case, the company may have the option to provide a diminished service.

Beginning 1/1/2020, companies can face a maximum penalty of up to $7500 for each violation that is not addressed. Additionally, if a data breach occurs, the law permits consumers to recover up to $750 per incident (or actual damages, if greater). A breach the size of Equifax could incur penalties of over 750)!

What does this mean for test and development data?

The broad definition of sensitive data covers most production data. This means that if a company wants to continue to use production data in testing and development, they will need to add a lot of process to be legally compliant, i.e., auditing, additional security, and user consent.

Some argue that using any data covered by CCPA in test is illegal because it’s performing additional processing on the data without consent. (note: we are not your lawyers)

Ok, what can I do?

- PURGE!!!! — you could delete all of your data from test, but you’ll likely need to replace it with something

- De-identify your data — you can modify your data so that it is no longer covered by CCPA

- Get user consent — you could notify all affected users and continually update them on infrastructure and usage changes

Ultimately, you must choose what’s best for you and your business. Production and subsets of prod typically yield the highest fidelity test results, but pose substantial risk to the business. Other techniques take time but usually trade off on cost or quality.

At Tonic, we believe synthetic data with the right tooling is the best solution because it allows you to drive costs down to manageable levels, while reaping all the benefits of using production data. If you’d like to learn more about our platform for generating synthetic data, drop us a line at hello@tonic.ai.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)